Farmers and Queer People: An Unlikely Alliance Sparked by the Impeachment Crisis

- lgbtnewskorea

- Jul 30, 2025

- 8 min read

In December, during a crisis of democracy triggered by Yoon Suk-yeol, farmers and queer people formed an unexpected and unprecedented alliance.

English Translation: Juyeon

Translation review: -

Writer of the original text: Miguel

Review and amendments to the original text: -

Web & SNS Posting: Miguel

News Card Design: 가리

Queer people and farmers?

In South Korea, queer communities and farmers have rarely been seen as groups with overlapping interests. While both are marginalized populations that have raised their voices in pursuit of rights—and while solidarity among marginalized groups has always existed to some extent—the idea of these two groups joining forces likely felt unfamiliar, even strange, to many.

However, in December, during a democratic crisis set in motion by Yoon Suk-yeol, farmers and queer individuals forged a surprising and unlikely alliance. This article explores how this alliance came to be—how, in opposition to a president whose rise to power was built on hatred toward minorities, farmers and queer people found common ground. We also take a closer look at Namtaeryeong, a place that came up repeatedly during the impeachment movement.

Queer voices in the impeachment movement

We’ve already covered how queer individuals consistently made their voices heard at the impeachment rallies against former president Yoon Suk-yeol. Yoon’s misogynistic politics—symbolized by his campaign pledge to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family—not only targeted women but also rolled back the rights of other marginalized groups, including people with disabilities, migrants, farmers, and LGBTQ+ individuals. It’s no surprise, then, that so many from these communities took to the streets in the face of his authoritarian threats, including talk of martial law. With far-right ideologies gaining ground worldwide, the threat of anti-democratic “emergency rule” became an especially acute and existential threat to marginalized groups.

Read more about LGBTQ+ voices in the wake of the “martial law” threat in LGBT News Korea: LGBTQ+ Voices Amid the Crisis of Human Rights and Democracy in the Face of a Military Coup

Even with all of this in mind, the prominence of queer symbols—like rainbow flags—at the Yoon impeachment rallies was still striking. Some have drawn comparisons to the 2016 impeachment of former president Park Geun-hye. Back then, LGBTQ+ people joined the movement with hopes of dismantling deeply entrenched systems of political and social corruption, but the post-impeachment reality was far from ideal. Under the Moon Jae-in administration, political agendas related to LGBTQ+ rights remained stagnant. Issues central to queer people’s lives—like the anti-discrimination law—were repeatedly pushed aside in favor of so-called “greater political causes.” And under Yoon’s administration, things only got worse.

That is why the abundance of rainbow flags seen at the Yoon resignation rallies can be understood as “both a reaction to the oppression and exclusion LGBTQ+ people experienced under the Yoon administration, and a powerful act of solidarity in resistance.” LGBTQ+ individuals took to the open mic platforms set up in the square to speak openly about their identities. In defiance of Yoon’s anti-minority stance, they called for inclusion as equal members of society, demanded the passage of anti-discrimination and marriage equality laws, and expressed solidarity with other marginalized groups.

Farmers in the impeachment crisis

One of the biggest issues for farmers under Yoon Suk-yeol’s administration was the proposed revision to the Grain Management Act. Originally enacted in 1950, this law enables the Korean government to intervene in key grain markets to stabilize prices. Rice, as the staple food for most Koreans, has been viewed as a crop the government must protect to ensure food security. As a result, the state has consistently encouraged rice production, and maintaining stable rice prices has been a core policy objective.

However, there are some challenges. One key issue is that whenever there’s a bumper harvest and rice supply increases, prices drop sharply—leading to a decrease in farmers’ income. This is because, under the current version of the Grain Management Act, government intervention in the market is optional, not mandatory. The law also lacks clear guidelines about when and how much grain the government should purchase. Another concern is the overreliance on rice cultivation, which has created a structural imbalance in agricultural production.

In 2023, the Democratic Party (DP)—then the opposition but holding a majority in the National Assembly—passed an amendment to the Grain Management Act, aiming to stabilize rice prices, protect farmers’ incomes, and strengthen food security. The revised bill included three key provisions:

Changing government intervention in the grain market from discretionary to mandatory,

Requiring the government to purchase surplus rice when overproduction exceeds 3–5% or prices drop by more than 5–8%, in order to stabilize the market,

And supporting the cultivation of alternative crops on land traditionally used for rice farming.

However, the ruling People’s Power Party (PPP) opposed the amendment, citing its inefficiency, violation of market principles, and fiscal burden. President Yoon Suk-yeol vetoed the bill—his first use of a veto while in office. After Yoon was impeached by the National Assembly, the bill passed again, but Han Duck-soo, then serving as acting president, also exercised a veto. At the time, the Constitutional Court had yet to rule on Yoon’s impeachment. Farmers were outraged and led tractor caravans to the capital, demanding Yoon’s impeachment and protesting the repeated vetoes of the bill.

Farmers and queer people meet in Namtaeryeong

On December 21, 2024, farmers driving their tractors from across the country toward Seoul were blocked by police at Namtaeryeong—a key entry point into the capital located on the border between Seoul and Gyeonggi Province. The police shut down all lanes at Namtaeryeong and attempted to forcibly suppress the farmers’ protest.

In response, a wave of marginalized people rushed to the scene in solidarity. As news of the standoff spread on social media, reports described how “within just an hour or two, thousands of young people” and “women in their 20s and 30s, waving the same light sticks they had held while singing ‘Into the New World’ in front of the National Assembly,” gathered in Namtaeryeong. Many of them had already been participating in impeachment rallies outside government buildings and the presidential residence—but upon hearing what was happening, they redirected themselves to Namtaeryeong.

Many queer individuals were there as well. Just as they had done at the Yoon impeachment rallies, they expressed their identities through speeches and flags—marching alongside other marginalized groups with rainbow flags held high, as if at a queer pride festival. They sang songs, stood their ground, and took turns speaking at the open mic.

“When women in their 20s and 30s began pouring into Namtaeryeong, the farmers were overwhelmed—stunned and deeply moved beyond what anyone could have imagined. [...] The organizers invited anyone who had something to say to come up on stage. People lined up to speak. One person who signed up to speak at dawn didn’t get the mic until 3 p.m. That’s how it was at Namtaeryeong—everyone was both a speaker and a listener.”

Their stories were diverse, but shared a common thread: they spoke about the discrimination and marginalization they had experienced in Korean society. A woman from Gwangju tearfully recalled how she once practiced speaking in a Seoul accent by clenching a pen between her teeth. A woman farmer from South Chungcheong Province criticized progressive intellectuals for looking down on rural communities. A young farmer took aim at the government’s overemphasis on smart farming policies. Feminists, LGBTQ+ people, and a young Chinese national who was raised in Korea also took the stage. One participant who stayed overnight at Namtaeryeong said, “Farmers, women, and young people taught each other through their stories. It felt like a 28-hour-long school had opened.”

(Source: SisaIN)

In the end, this wave of solidarity forced the police to back down. At 4 p.m. on December 22, they dismantled the barricade and allowed 10 of the 30 tractors to enter Seoul. The tractors continued their protest, heading toward the presidential residence. Ha Won-oh, chair of the Korean Peasants League (KPL) which led the tractor demonstration, called it “a victory made possible by women, queer people, youth, the elderly, the urban poor, and farmers—all those who have been excluded from mainstream society through hatred and discrimination.”

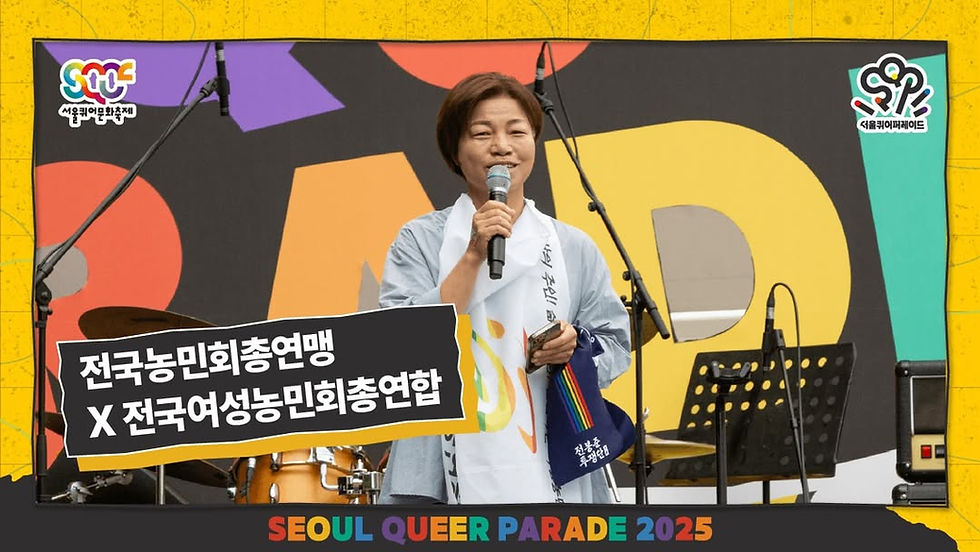

Farmers and queer people meet again at the queer culture festival

On June 14, farmer organizations including the KPL and the Korean Women Peasants Association (KWPA) set up booths at the Seoul Queer Culture Festival (SQCF). This was a gesture of solidarity in response to a speaker at the presidential impeachment rally who had said, “I hope the farmers will come to the queer culture festival” during an open mic speech.

The farmer groups hosted a variety of activities at their booths: they explained agricultural issues through quizzes, conducted surveys on the right to food, and handed out fresh produce harvested from across the country. Rev. Cha Heungdo, a rural pastor, once again offered blessings for LGBTQ+ couples. Festival attendees welcomed the presence of the farmer organizations, many of them recalling the powerful moments shared at Namtaeryeong during the impeachment protests.

To close, let us reflect once more on the meaning and power of the solidarity shown between queer people and farmers—through the words of Jeong Youngyi, Chair of the KWPA, spoken at the Seoul Queer Culture Festival:

“Like many of you, farmers have always been a minority. Our struggles have always been lonely. Whenever prices rise, agricultural products are blamed. In every trade agreement, it’s agriculture that’s sacrificed. Our voices have been silenced, and we’ve been forced to endure endless sacrifice.

But at Namtaeryeong, things were different. You ran to our side without a moment’s hesitation. You offered unconditional solidarity with our fight. From the first Namtaeryeong protest to the second, and all the way until the moment Yoon Suk-yeol was removed from office, our friends from marginalized communities stood with us.

Note: “First Namtaeryeong” refers to the protest on December 21, 2024, as described earlier. “Second Namtaeryeong” refers to the protest on March 25, 2025, when farmers once again drove tractors to Seoul to protest the delay in Yoon Suk-yeol’s impeachment ruling, and were blocked by police at the Namtaeryeong checkpoint.

Farmers experienced something new at Namtaeryeong—a vision of an equal world that transcends differences in race, ability, education, wealth, region, and gender. We learned so much from that moment.

However, the reality is that the countryside remains one of the most patriarchal places in our society. Women farmers are the primary producers of agriculture, yet we are still denied proper legal and social recognition. After 30 years of living in the countryside—fighting discrimination, hatred, and oppression, and calling for equality—I sometimes wonder, ‘Is this all we’ve managed to change?’ I feel ashamed. I feel sorry.

Still, we will continue, as we always have: cultivating the land and strengthening our organizing. Women farmers will transform the encounters between women and queer people at Namtaeryeong into ongoing solidarity. Through food sovereignty, we will work to ensure that all people have the right to access equitable, just food.

Revolution is born where diversity exists. Queer people must be recognized in rural communities as well. We will fight to protect the right to exist and live free from discrimination. This world will be changed by people like us—the marginalized, the excluded. And in that journey toward a world without discrimination, women farmers—and farmers—will be with you.”

English Translation: Juyeon

Translation review: -

Writer of the original text: Miguel

Review and amendments to the original text: -

Web & SNS Posting: Miguel

News Card Design: 가리

References (available in Korean)

김세희. 2025년 1월 30일. 「탄핵 시위에 왜 이렇게 무지개 깃발이 많냐구요?」. 오마이뉴스. https://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/View/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0003099710

이오성. 2023년 4월 25일. 「양곡법 거부, 대통령이 사상 처음으로 농민을 걷어찼다」. 시사인. https://www.sisain.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=50146

2024년 12월 20일. 「한덕수 대통령 권한대행이 거부권 쓴 '양곡법 개정안'은 무엇?」. BBC 뉴스 코리아. https://www.bbc.com/korean/articles/cy4pj9w54nyo

이오성. 2025년 1월 6일. 「서로를 가르친 28시간, 남태령은 ‘학교’였다」. 시사인. https://www.sisain.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=54716

임은경. 2025년 6월 7일. 「“차별받는 소수자들이 세상을 바꿀 거예요”」. 프레시안. https://www.pressian.com/pages/articles/2025060412264045704

박주연. 2025년 1월 4일. 「‘남태령 대첩’ 이후, 여성과 소수자가 열어갈 세상」. 일다. https://www.ildaro.com/10085

강선일. 2025년 6월 19일. 「‘무지개 축제’ 초대받은 전봉준투쟁단, 성소수자 친구들과 재회」. 한국농정신문. https://www.ikpnews.net/news/articleView.html?idxno=67553

명숙. 2024년 12월 24일. 「[명숙 칼럼] 남태령의 밤, 우리의 투쟁은 다른 세상으로 나아가고 있다」. 민중의소리. https://vop.co.kr/A00001665531.html

고은. 2024년 12월 26일. 「소수자 연대가 새로 쓴 역사, 남태령 대첩」. 주간영동. https://www.bluestars.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=5016

Comments